The open source software movement has evolved dramatically over the past two decades. Many businesses that once considered open source a threat now recognize its value.

On the other hand, in spite of increased enthusiasm among enterprises, consumer interest by and large has not materialized.

With large companies increasingly embracing open source, what does it mean to be a part of the free and open source software, or FOSS, “community”?

Why have consumers been so slow to adopt open source software?

Our roundtable of industry insiders tackled those questions during their lengthy virtual conversation on technology trends.

Participants in the discussion were Rob Enderle, principal analyst at the Enderle Group; Ed Moyle, partner at SecurityCurve; Denis Pombriant, managing principal at the Beagle Research Group; and Jonathan Terrasi, a tech journalist who focuses on computer security, encryption, open source, politics and current affairs.

A Chaotic Community

For enterprises, adoption of open source “means better control and understanding of the code they use and how it is progressing,” said Rob Enderle. “In effect, it lowers their operational risk IF they properly fund the effort. If they don’t, it results in a bigger exposure due to the misuse of these tools.”

“Big companies have taken on fully commoditized infrastructure tech. That’s normal and it will continue,” said Denis Pombriant.

Being part of the FOSS community “really just means providing value back to others in whatever way you’re able,” offered Ed Moyle. “This can be as a developer but also as a user, tester or financial supporter. Anyone providing value back — small or large — is part of the community.”

The freedom in adapting open source to one’s own particular needs — one of the hallmark principles of the FOSS movement — can pose problems for a community that is at best loosely knit.

“Considering the degree to which bigger tech companies with traditionally proprietary models are incorporating open source projects, the FOSS community looks to be on course for a schism,” warned Jonathan Terrasi.

“The Linux Foundations and the Red Hats of the community will likely keep progressing in the direction they’re headed, while smaller scrappier projects with more ideological grounding in FOSS will eschew those projects and go their own way,” he predicted.

“With each set on their own course, their challenges will be different,” Terrasi continued.

“In the former case — that of the standouts in FOSS, like Linux — their job will increasingly center on balancing the demands of very different clients, such as Microsoft and Google in Linux’s case,” he said.

“For the latter case, the obstacles are less foreseeable, but will probably have to do with keeping from getting starved for oxygen when their larger cousins scoop up most of the corporate investment,” Terrasi speculated.

Those cautionary notes aside, “now is a really exciting time in open source,” maintained Moyle.

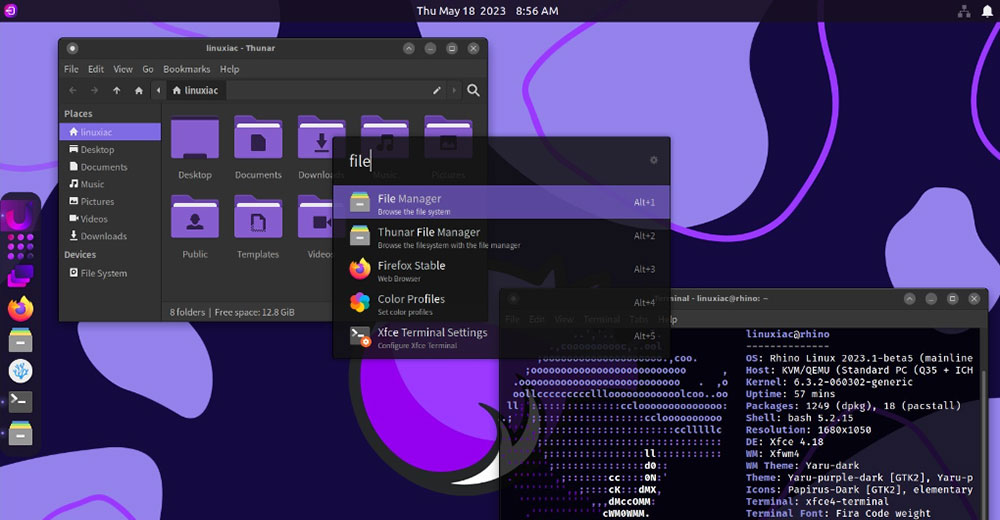

“Everything DevOps is open source: Source control (git), CI/CD (jenkins, ansible), containers (docker, rkt), orchestration (kubernetes). Desktop Linux is more viable than it’s ever been, and Linux is the primary cloud platform, by a wide margin. That’s the positive side, and it’s tremendously exciting,” he said.

“The less positive side, though, is that there’s a trend of ‘faux-pen source’ projects out there that seem to be increasing in prevalence,” observed Moyle.

“By this I mean one of two things: 1) projects that claim to be open source and are marketed or hyped that way, but that have bogus — that is non-free — licenses; or 2) where the source is technically open, but the functionality is broken in some fundamental way unless you pay someone money,” he explained.

“I have NO problem with someone wanting to make a buck for their work,” Moyle emphasized.

“For example, a company charging for support, charging for additional data and services — in the security world, for example, charging for signatures/rules, etc. These are all reasonable to me,” he said.

“But it does really irritate me when something is released as ‘open source,’ seemingly for marketing purposes, but in order for it to do anything useful you need to pay someone money. While such an offering might adhere to a strict reading of a free license, it’s hard to argue that it’s in keeping with the ‘free and open’ community-based nature of open source. It seems disingenuous to me,” Moyle said.

“I had never heard of the ‘faux-pen source’ moniker, but it is a pithy term for a real phenomenon,” Terrasi responded.

“I wholly agree that people should be paid for their work, but as Ed put it, it is disingenuous to lean on the goodwill that open source communities strive to engender as a way of deriving revenue,” he added.

“There is no doubt that open source software enjoys better representation now than it ever has — even the Linux desktop — but this may owe partly to the exploitation of FOSS’ conspicuous weaknesses of being free and open,” Terrasi suggested.

“Because they are open, they invite any code contribution of sufficient merit, and because developers need to eat, they invite any monetary contribution whenever feasible,” he pointed out.

“However, larger companies exploit this to swoop in, colonize the code and/or funding base, and then take control of the project from within. A recent article about Twitter’s Bluesky project quoted experts who warned of exactly that phenomenon,” Terrasi said. “The challenge going forward will be for FOSS projects to reconcile continuing to exist with preserving the integrity of their mission.”

Consumer Resistance

There’s a simple reason for low consumer interest in open source software, suggested Enderle.

“They aren’t coders,” he said.

Open source is “mostly infrastructure,” noted Pombriant.

“Customers still need service, and therefore adhere to brands and their support. Open source is problematic from a business model approach and from a customer service one,” he maintained.

“As far as the open source revolution has come, there are still pervasive misconceptions surrounding it,” said Terrasi.

“There is still the unfounded but stubborn perception on the part of the consumer that open source software is insecure, that because it’s ‘free’ the quality is inferior — in the vein of the old adage ‘you get what you pay for’ — and that it’s not as flashy or glossy,” he continued.

“I think most developers know better than to buy into these myths, but because their customers don’t, they’re not going to try to deliver open source products over their customers’ objections,” Terrasi reasoned.

“Frankly, there have been, and still are, significant barriers to entry for many FOSS tools,” Moyle pointed out.

“For example, I use Linux as my primary platform and it’s a nonstop PITA — I say this lovingly,” he said.

“The ongoing challenges are legion. For example, the integrated fingerprint scanner on my laptop doesn’t work — no drivers. I’ve had to tweak the BIOS to get it to run appropriately. I’ve had to write code to get dual monitors to work, make changes to support HDMI audio output, etc.,” Moyle said.

“For many orgs, the hassle factor of having to deal with these tweaks yourself — not just in Linux, but in any FOSS that is primarily community driven — is more expensive than paying a vendor for a COTS alternative. This is why you see such an uptick in open source that has industry backing: docker, SaltStack, Kubernetes, etc. — because that minimizes the hassle,” he explained.

“For me it still comes down to consumers not having, and not wanting to develop, the needed skills,” Enderle said.

“Working on things is becoming a lost art. I’ve had kids ask me what an air cleaner on a car is. To the younger generations, much of what they get is kind of like magic. It just works, and they don’t really care how until it doesn’t — and then they only want someone else to fix it. Granted, with some of the newer complex technical products that is probably the safer path,” he added.

“My Linux use has very seldom required anything so drastic as what Ed has encountered, but I know that it can definitely break down like that,” said Terrasi.

“Linux has come a long way, and there are definitely distros that are as stable as any consumer would expect their operating system to be, but the bad press from Linux’s Wild West days has taken its toll,” he noted.

“Also, at least with open source OSes — namely Linux — I think there’s just a real apprehension about changing one’s system that fundamentally. There’s this idea many users have that the developers who made the device know best and have your best interests at heart, so you shouldn’t contravene them by installing your own OS,” Terrasi observed.

“It’s this deference to authority — in a specific context — that is weirdly dissonant with a social climate right now where perceived ‘elites’ are distrusted in favor of the expressed will of the community of non-elites, but it’s a real thing and you see it every day like in the way people flock to the Apple Genius Bar and unconditionally trust the intentions of a roughly (US)$1 trillion company,” he pointed out.

“Open source on the whole, and Linux in particular, are never going to enjoy any home consumer market share to speak of until that misconception is overcome,” Terrasi maintained.

Aside from the technical difficulties consumers may encounter with open source, there’s the issue of visibility. Many consumers may not even be familiar with the term, much less with what it means.

“It’s difficult for open source projects to market and advertise the same way that closed-source technology vendors do,” noted Moyle.

“It’s also difficult for them to use the same techniques to gain marketshare — for example, establishing VAR arrangements or channel partnerships,” he said.

“From an end-user point of view, the support experience is a whole different ballgame. If a commercial product doesn’t work or has an issue, you can work with someone directly to solve the problem,” Moyle said.

“In the open source world, the onus is on you in many cases to solve your own problem with support from the broader community. This can be a tall hill to climb for someone with little or no technical expertise,” he pointed out.

“I concede that the lack of support is a a genuine and understandable barrier,” said Terrasi.

“I don’t see Canonical setting up ‘Einstein Lounges’ anytime soon. I do take some solace in the fact that we live in an age where no one makes a purchase without reading numerous online reviews and, jointly, in the fact that some of the beginner-friendly Linux distros have welcoming and knowledgeable communities who want newcomers to stick around,” he added.

“I’m not proclaiming the Year of the Linux desktop anytime soon,” Terrasi said, “but taking Linux as an example, there are some things that open source projects are doing right to attract users from the mainstream consumer base.”