There has been a lot of debate in the public sphere around the degree and kind of legal regulation a society should apply to online speech. While the dialogue has become more intense and urgent in the last few years, the effort to impose limits on Internet speech has been contentious from the start. At the present juncture, Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act is undergoing reconsideration.

It’s easy to take knee-jerk stances on Internet speech regulation, but they generally do not achieve as satisfactory or sustainable end results as stances that are grounded in an appreciation of history. In fact, it is precisely hasty judgment and foggy understanding of the Internet’s sheer novelty that got us to this fractious juncture in the first place.

That’s why I want to present a brief overview of Internet regulatory history: to do my modest part to set the conditions for more enlightened outcomes. I owe much of the research that informs this treatment to a book called Blown to Bits, by Hal Abelson, Ken Ledeen and Harry Lewis.

If you are interested in getting a fuller, but still digestible, understanding of how radically new and unprecedented the Internet is, it is worth checking out, which you can do for free (it’s licensed under Creative Commons).

The Wild Wide Web

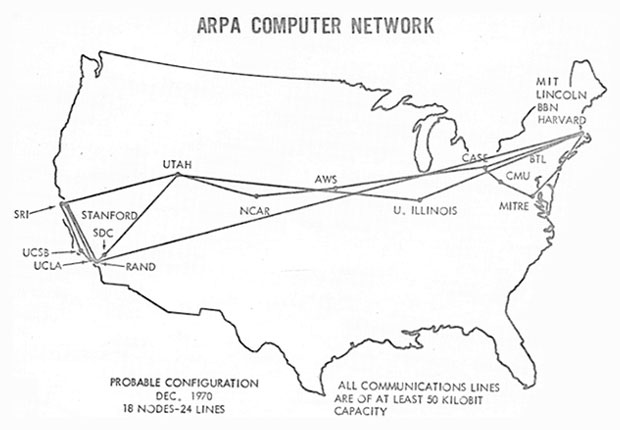

Let’s start at the beginning, but we won’t spend too much time there. The Internet began in the 1960s as a military research project run by the Advanced Research Projects Agency, or ARPA, which since has been renamed “DARPA” (the “D” standing for “Defense”). It was devised as an outage-resistant communications medium, so that the downing of strategically placed telecommunications nodes would not prevent messages from being sent.

To be precise, it was meant to be an alternative to traditional telecommunications, like telephone lines, which would fail if the Soviet Union leveled the right city.

The Internet accomplished its goal brilliantly, and it still does what it was built to do. It effortlessly reroutes data packets on the fly, without a centralized architecture, to get them where they’re going as long as any path between the source and destination exists.

To test this, ARPA partnered with the country’s most prestigious universities and research firms and linked them all together. For a while, the only people on the Internet were the researchers at those institutions, as this 1970 map of the Internet shows.

By the 1980s, the Internet opened to the public, but it was so arcane and inaccessible that only a small cadre of private and public sector players — and, as it turned out, their family members — had any contact with it. Home computers ran in the thousands of dollars, making them impractical to most but obtainable for some. Large corporations had started using the Internet as part of their operations, so some of their employees followed suit at home to get in more practice.

Government-employed computer scientists were among the first to have Internet-connected devices in the home. A lot of the first wave of hackers, as well as progenitors of “cyberspace” culture overall, were the children of those professionals, who used their parents’ devices to rove around the bulletin boards of the early Web.

Computers really proliferated among consumers in the 1990s. Email started to be a regular part of the lives of American adults. However, by the time consumers — and crucially legislators — first encountered abusive online behaviors that merited regulation, a robust tradition of total freedom already had taken root.

Bulletin board services were accustomed to operating without interference, and Internet service providers (ISPs) were content to deliver the bytes and leave the rest to someone else.

It was the dissonance between the reluctance of longtime users to give up their taste of freedom and the outcry from consumers and politicians appalled by the abuses of a few that begot the whiplash in Internet regulation.

There’s a Sheriff in Town

There were really two types of content that shaped speech on the Internet: defamatory content and obscene content, especially any that could harm children. In the analog world, many different parties must work together to facilitate the expression of speech, but they bear different degrees of legal responsibility for objectionable speech.

Authors always bear the greatest responsibility, since the speech is their own. Publishers are also responsible, because they wield editorial control over the author’s words, meaning they know what the authors they publish are saying and, by extension, signed off on it.

Distributors generally aren’t held culpable, because they usually don’t know, and aren’t expected to know, the content they are distributing. Think of newspaper delivery kids: It’s not their job to read the newspaper and make sure it doesn’t contain any falsehoods or obscenities.

These categorizations of parties in the content production chain seem reasonable and intuitive enough, but what lawmakers, judges and Internet users found was that applying them to the Internet was no simple matter.

In trying to bend the Internet content apparatus into a shape resembling the analog one, lawmakers generally can regulate only a few parties.

They can regulate authors who reside within U.S. jurisdiction. Alternatively, they can regulate the author’s ISP, but also only if it operates within U.S. jurisdiction. Finally, lawmakers also have the option of regulating the consumer’s ISP and consumers themselves, based on the assumption that the consumers are in the U.S. (just as Americans benefit from U.S. anti-defamation and anti-obscenity statutes due to their assumed physical residence within the reach of U.S. law).

A legal scuffle between two online bulletin board services in 1991 marked the first time that U.S. courts affirmatively affixed a classification — author, publisher or distributor — to an online player. Back then, the company CompuServe maintained a rumor forum, Rumorville, which posted content provided by third parties. The key detail is that CompuServe did not review any of the material it received — it merely posted whatever its contracted content producers provided.

Another bulletin board operator, Cubby, propped up Skuttlebut, a competitor to Rumorville. Shortly afterward, a rumor cropped up on Rumorville alleging that Skuttlebut was phony, and because Cubby saw this as CompuServe spreading falsehoods to edge it out, Cubby sued CompuServe for defamation.

In Blown to Bits, the authors characterize the case this way: “Grasping for a better analogy, the court described CompuServe as ‘an electronic for-profit library.’ Distributor or library, CompuServe was independent of [its content creator] and couldn’t be held responsible for libelous statements in what [the creator] provided. The case of Cubby v. CompuServe was settled decisively in CompuServe’s favor.”

In other words, when the dust settled, online platforms were deemed to be distributors, meaning they were off the hook for any objectionable content their users or providers transmitted via their platform.

That’s why the next landmark court case took online platforms completely by surprise. It started out in much the same way as Cubby v. CompuServe, with a bulletin board getting hit with a libel suit. In 1994, an anonymous user on Money Talk, a finance-focused board owned by Prodigy, accused the firm Stratton Oakmont of “major criminal fraud.” Stratton Oakmont sued Prodigy for libel, begetting Stratton Oakmont v. Prodigy.

That case came with a twist: Eager to engender a family-friendly atmosphere on its boards, Prodigy openly advertised that it moderated its platforms to scrub them of obscene content. The court found that detail compelling, and it ruled in favor of the plaintiff.

“By exercising editorial control in support of its family-friendly image, said the court, Prodigy became a publisher, with the attendant responsibilities and risks,” wrote Abelson et al.

To the court, it did not matter that fact-checking went beyond the scope of Prodigy’s intentions through its moderating. If a platform moderated at all, it took on an editorial role, which would make it liable for anything and everything it hosted. Thus, the decision discouraged bulletin board services from taking on any editorial duties, lest they find themselves on the hook for objectionable content.

The Perfect Torrent

Would you believe me if I told you that an ethically suspect scientific study, sensational journalism, and overzealous senators led to the most influential Internet speech law ever passed?

Strange as it sounds, that’s exactly what happened.

A shocking cover expos, “CYBERPORN,” was published in Time magazine on July 3, 1995, and it immediately set off moral panic in Washington. It later emerged that the researchers behind the study at the heart of the story used unethical methodologies.

For example, they compensated participants for providing material that reinforced the author’s confirmation bias (that the Internet was rife with pornography), and published their work in what masqueraded as a peer-reviewed journal but was little more than a student paper.

Those in Congress seeking to stem the tide of profane Web content found themselves in a jam, because after Stratton Oakmont v. Prodigy, no one wanted to touch content moderation. The result was the near-unanimous passage of the Communications Decency Act, or CDA, in 1996.

The law had two key components — the “display provisions” and the “Good Samaritan provision.”

The display provisions took aggressive aim at “obscene and indecent” content that could end up on a screen in front of a child. Among other things, the display provisions made it illegal for “any interactive computer service to display in a manner available to a person under 18 years of age, any comment, request, suggestion, proposal, image, or other communication that, in context, depicts or describes, in terms patently offensive as measured by contemporary community standards, sexual or excretory activities or organs.”

Additionally, the law included a Good Samaritan provision, which makes up the heart of Section 230 (and which “Section 230” generally is invoked to reference). Its language accomplishes two significant feats.

First, it shields any “interactive computer service” from liability for the consequences of making good faith efforts to remove “obscene, lewd, lascivious, filthy, excessively violent, harassing, or otherwise objectionable” content.

Second, it classifies these services as “distributors” in the meatspace analogue: “No provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be treated as the publisher or speaker of any information provided by another information content provider.”

The ACLU challenged the CDA in ACLU v. Reno on the grounds that it unduly limited legitimate First Amendment speech, and got the display provisions struck down as unconstitutional.

As Judge Stewart Dalzell stated in the majority opinion, “It would chill discourse unacceptably to demand age verification over the Internet from every person who might see material that any adult has a legal right to see.”

The crux of the defense’s case was that the Internet should be regulated the way TV is, but the court rejected the comparison as inapt.

“The Internet may fairly be regarded as a never-ending worldwide conversation. The Government may not, through the CDA, interrupt that conversation. As the most participatory form of mass speech yet developed, the Internet deserves the highest protection from governmental intrusion,” Dalzell wrote.

Good Samaritans, Questionably Good Outcomes

Notably, the Good Samaritan language of Section 230 was left intact in the ACLU decision. Although this is the regulation public discourse now swirls around, that case did not mark the first time it sparked controversy. Indeed, problems emerged immediately.

One test of the law played out in 1997 when Matt Drudge posted allegedly defamatory statements about Sidney Blumenthal, an aide to President Bill Clinton at the time, on AOL. Though AOL had editorial influence over the Drudge material it posted, the court ruled that the company was not a publisher, and therefore was not liable for libel. The opinion cites the CDA’s Good Samaritan language.

In 1998, Jane and John Doe (in this case, a mother and her son) sued AOL because it allowed a user to sell pornograhic material made of John when he was a minor. In its user agreement, AOL reserved the right to terminate service for any user who engaged in abusive behavior. The Good Samaritan provision also was cited in that case to absolve AOL of responsibility.

Abelson et al. sum up the problem: “Congress had made the muddle possible by saying nothing about the right analogy after saying that publishing was the wrong one.”

The Law of the Cyberland

With this historical overview complete, we are more or less caught up to the current technological epoch.

Section 230 remains one of the few forces incentivizing content moderation among online platforms. The fatal flaw here is that so long as they can argue convincingly that their actions were in good faith, they are immune to legal consequences.

Granted, it has been established that online services lose their liability protection if they are notified of the commission of federal crimes or intellectual property theft and take no action, but Section 230 is nearly absolute otherwise.

As a result, online platforms have wide latitude to create and enforce whatever community standards they choose. If the speech standards enforcement is excessive, deficient or lopsided, a platform’s operator can hide behind the good faith defense, innocently claiming that nobody’s perfect.

True as that may be, free speech advocates contend that should not serve as a blank check to decide arbitrarily who can “speak” on a platform, and on what terms.

The other contributing factor is, as I like to say, “there are no sidewalks on the Web.” Nearly the whole of the Web — specifically the Web, as distinct from the Internet — is private property. The First Amendment restrains the government from censoring Americans’ speech.

Because sidewalks, for example, are public property, the government can’t tell you what you can and can’t say while you’re standing on one (with a few exceptions for public safety). However, the First Amendment does not apply to private entities, which is what most Web platforms are. If you register to a social network, you consent to its rules, including those that prohibit certain kinds of speech.

Just as the Web of the 80s and 90s was settled by pioneers, only for lawmakers to catch up gasping for breath, the trailblazers have kept pushing on to leave civil servants in the dust once again. Measures that seemed robust enough in the late 90s are beginning to groan under the weight of newer and more sophisticated usage patterns on the Internet.

Daunting as it is to keep up, as members of a society we must do our best, which requires an appreciation of how we got here. The alternative is to make decisions on the spur of the moment, which are unlikely to withstand the test of time, and too likely to wreak havoc along the way.